For our next book on the NHL Executive Reading List (click here to read about the list), we stick with baseball and dig into Astroball by Ben Reiter (Amazon).

Reiter’s story and the impetus for this book is pretty amazing in itself. Here’s a quick recap from the book cover:

When Sports Illustrated declared on the cover of a June 2014 issue that the Houston Astros would win the World Series in 2017, people thought Ben Reiter, the article’s author, was crazy. The Astros were the worst baseball team in half a century, but they were more than just bad. They were an embarrassment, a club that didn’t even appear to be trying to win. The cover story, combined with the specificity of Reiter’s claim, met instant and nearly universal derision. But three years later, the critics were proved improbably, astonishingly wrong.

Yes, the Houston Astros won the World Series in 2017, exactly as Reiter had predicted.

I first came across this book through Shane Parrish (@ShaneAParrish) and it’s been one that multiple hockey executives have since recommended to me privately. Similar to The Cubs Way, it offers a blueprint for building a World Series champion in the modern era of baseball. The Astros and Cubs shared some analytical philosophies, but Reiter dug up plenty of new insights around decision making that made this book a worthwhile read.

Here are my five key takeaways:

(1) Synthesizing Information to Make Better Decisions

Jeff Luhnow (General Manager) and Sig Mejdal (Director of Decision Sciences at the time) serve as the key characters in the Astroball narrative.

Luhnow, a former McKinsey consultant who also spent time in the St. Louis Cardinals front office, had a vision of synthesizing all of the various inputs used by baseball teams to evaluate players into a reliable decision making model. Scouting reports, performance data, health information, etc. This ideal system would capitalize on the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative sources while also mitigating the risks associated with each type of information.

Mejdal was tasked with delivering on that vision.

The Astros — like the Chicago Cubs — believed in collecting as many data points as possible, but it was important to keep those inputs simple and consistent. Mejdal proclaimed that “if a human being can sense it, a human being can quantify it. If he can quantify it, he can learn about it.”

Mejdal organized all of the information he could find dating back over 20 years and ran regressions to understand the most important variables:

The idea was, essentially, to systematically scout the scouts in order to determine which of their judgments had real predictive value and which were the product of cognitive biases—and then to properly weight them along with the performance data by comparing that universe of attributes against those of players who had once performed or been judged similarly.

The regression exercise is one that all professional baseball organizations have probably done to one extent or another. It’s the data process at the heart of the ‘Moneyball’ story — an attempt to find value in overlooked places by letting the data tell you what really matters.

I figured the Astros would use their findings to provide feedback to scouts about how cognitive biases are causing them to overrate or underrate certain types of players. But that wasn’t the case at all:

“They’re not trying to ask us to be sabermetricians,” said Ralph Bratton, a Texan with a thick white mustache who became an Astros scout in 1990. “They’re asking us to do what we’ve always done.”

Luhnow and Mejdal accepted that cognitive biases are going to be tough (or maybe impossible) to eliminate in a scout like Bratton, who has been doing his job a certain way for nearly three decades. They wanted Bratton to stick to his process, even if that meant overrating players from Texas or underrating players from Latin America, for example.

They wanted Bratton to stay in his lane, relying on his experience and intuition. Mejdal’s job was to “merge the lanes” and adjust for biases.

(2) Understanding the Limitations of a Decision-Making Model

The Astros believed that one of their biggest competitive advantages was “having the discipline and conviction in our information to stick with it even when it feels really wrong.”

It’s easy to say you want to optimize your decision making. It’s also easy to support a decision making model that spits out an optimized recommendation that aligns with your initial hunch. The defining moment for any organization is when it comes time to make a multi-million dollar decision based on a model that cuts against your gut and intuition. Make a ‘wrong’ decision and that’s a strike against you in the eyes of the media or ownership. Make enough ‘wrong’ decisions and you’re probably looking for a new job.

Danny Heifetz at The Ringer recently wrote a history of the analytics movement in football and interviewed Frank Frigo of Edj Analytics. As an NFL outsider, Frigo was shocked to find that teams weren’t interested in implementing his recommendations, even if they were backed by strong probabilistic reasoning:

“To come into this NFL culture where all of a sudden I’m finding out that there’s other motivations that aren’t necessarily perfectly aligned with win probability was a real eye-opener for me. First of all, there’s these other sort of risk-management considerations and biases that [coaches] have. Secondly, they just don’t think probabilistically. I mean, that’s the part that struck me.”

Even in the statistically-advanced world that is baseball in 2019, there are still plenty of examples of outright defiance. The New York Mets hired Adam Guttridge as Assistant GM of Systematic Development earlier this year in an attempt to catch up to data-savvy teams like the Astros, but six months later Mets manager Mickey Callaway said “I bet 85% of our decisions go against the analytics and that’s how it’s always going to be.”

Reiter captured the essence of the struggle in a great line at the end of Astroball: “Data could help guide best practices, but it was unwise to confuse those with perfect practices.”

No decision making model is perfect, especially when you’re dealing in probabilities.

The Astros failed to appreciate the changes JD Martinez made to his swing one offseason and Martinez was released by the team in 2014. He’s since gone on to become one of the best hitters in Major League Baseball and was most notably a critical piece of the Boston Red Sox World Series win in 2018.

Was losing Martinez for nothing a mistake? In one sense, absolutely, and the Astros admit that.

Luhnow also saw it as an opportunity. Any model relying on historical data points and regression analysis will have trouble identifying outliers like Martinez who are moving forward on a new talent trajectory. Sometimes the quantitative data will say “he’s finished” while the qualitative inputs violently disagree (Martinez insisted he had changed for the better).

Disagreement between inputs wasn’t a bug in the system, as Reiter explained. It was a feature.

Chuck Fletcher, GM of the Philadelphia Flyers, echoed similar sentiments when asked by Pierre Lebrun at the Athletic how he balances scouting reports and analytics:

“You need data. You need to make informed decisions. And ideally you’re combining the data with strong scouting opinions. You’re trying to make sure you cover all the bases. It’s something certainly that I utilize. But I would assume every general manager does at this point. Just to give you a different perspective and ideas and oftentimes the two are very similar: what the scouts see and what the data tells you. When there’s a difference of opinion that’s sometimes where the value is.“

(3) Diverging from the Model

The book highlighted a number of situations when the Astros front office clearly acted against the advice of their decision-making model.

In the case of acquiring Justin Verlander at the 2017 trade deadline, Luhnow and Mejdal suspected their model wasn’t appropriately valuing the complex options in Verlander’s contract. Luhnow also acknowledged that there are moments when you have to act in a way that doesn’t perfectly align with the most optimal solution:

“The reality is that any economic modeling which includes projections is not going to like a deadline deal, where you’re trading what could be an enormous amount of future value for a decent amount of present value. The question all general managers have to grapple with is, how much of a deficit can you take on one deal?”

Taking lessons from the Verlander example — and Houston’s subsequent World Series win — makes for great narrative but is classic survivorship bias. The reality is most deadline deals don’t result in a World Series.

My takeaway was that at least Luhnow had a rationale for why he was diverging from the model. He understood it well enough to identify potential flaws and was transparent with his staff on how he arrived at the decision.

He also empowered his scouts to highlight other opportunities for disagreement. Ahead of the draft, each scout received five gold star stickers called ‘gut feels’. The stars were tagged onto the names of players who the scout felt would outperform expectations, for whatever reason.

Think of every behind-the-scenes show you’ve seen with an NHL front office preparing for the draft. It usually features a scout passionately describing a certain player’s “compete level” or “make up” to justify an upgrade on the pre-draft list.

Luhnow was happy to listen to those same passionate speeches — which I assume allowed the scout to feel ‘heard’ as an actual human being — but the gut feel sticker idea fits so perfectly into the Astros process.

Remember Mejdal’s quote in the first takeaway? “If a human being can sense it, a human being can quantify it. If he can quantify it, he can learn about it.”

In the moment, basing a draft decision on a gut feel sticker is making a conscious decision to diverge from the model and trust a scout’s intuition.

Over the longer term, however, Mejdal now has a simple and consistent input that can be used to quantify and learn about that scout’s intuition.

Maybe Ralph Bratton, the scout with the white mustache, isn’t the most eloquent salesman but he’s developed a keen eye for identifying talent over his 30 years. Bratton doesn’t need to take a presentations course to improve his influence and persuasion abilities. He just needs to do what he’s always done.

If he really has expert intuition, Sig Mejdal will notice.

(4) Changing Trajectory Through a Growth Mindset

Astros GM Jeff Luhnow sees every draft class as a portfolio and like most investors he prefers a diversified approach.

“You’ve got to mix up some big bets with some fliers,” Luhnow said. “You’re going to have some hits and failures.”

The essence of most portfolio management strategies is maximizing return for a given level of risk. In order to maximize the return of a draft class, you first need to establish an expected value for each player.

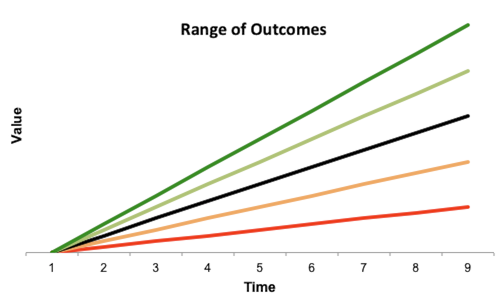

Every player’s career has a range of outcomes. Jack Hughes, the #1 overall pick in this year’s NHL draft could turn out to be Sidney Crosby. He could also turn out to be Patrik Stefan. In a simplified sense, the sum of all of these possible outcomes multiplied by the probability of each of them occurring gives us an expected value for Hughes.

Every player’s career has a range of outcomes. Jack Hughes, the #1 overall pick in this year’s NHL draft could turn out to be Sidney Crosby. He could also turn out to be Patrik Stefan. In a simplified sense, the sum of all of these possible outcomes multiplied by the probability of each of them occurring gives us an expected value for Hughes.

In the decade after the release of Moneyball in 2004, most baseball teams were leveraging data and analytics to improve their ability to evaluate players.

Theoretically, the more information we know about a given player, the more confident we can be in the probabilities we assign to each possible future outcome. Refined probabilities improve our expected value calculation and help us identify opportunities to “buy dollars for 40 cents,” as Warren Buffett would say.

What the Moneyball story underestimated was the ability for a player to influence his own trajectory. The Astros believed that player talent levels aren’t fixed. JD Martinez’s career trajectory wasn’t simply based on a roll of the dice. Data and analytics delivered in an actionable way could help Martinez (or any player) improve and launch himself into the higher range of possible outcomes.

But that also required finding players with the right attitude towards personal development. Carol Dweck, Professor of Psychology at Stanford, calls it a growth mindset and the Astros knew this characteristic was critical:

Luhnow believed that…their analytics-aided tactics and training methods would provide those players with the tools to succeed. At a certain point, the decisions were out of the front office’s hands. They belonged to the players themselves: how hard to train, what to eat, how willing they were to use those tools to determine which pitches to swing at and which to throw. That was where having a growth mindset was important. The [Astros] could provide a player at even the organization’s lowest level with data that revealed exactly how he might improve his plate discipline or the mix of his pitches to find greater success, but that was just the start of it. It was up to the player to have the willingness to act upon that information in order to grow.

For more insight on how the Astros and other baseball teams are moving aggressively into the player development space, be sure to read The MVP Machine by Ben Lindbergh and Travis Sawchik.

(5) The Carlos Beltran Factor

All of this talk of portfolio management and decision-making algorithms understates the importance of the human element in sports.

During the Astros’ 2017 World Series season, Carlos Beltran was a 40-year-old fading star. He earned $16 million and his batting average of .231 was a career low. Any economic model could tell you that’s not exactly a great return on investment.

Beltran’s off the field impact, however, was almost invaluable.

His experience allowed him to get inside the mind of a young teammate and understand why the player is struggling.

When feedback was necessary, Beltran’s peer status made it easier to deliver tough messages.

His spot on the field gave him a unique lens with which to analyze and identify the weaknesses of opponents.

And perhaps most importantly, Beltran was able to bring the Houston Astros together as a team. He made sure that younger teammates weren’t intimidated by his 9x All Star resume.

“My friend, I am here to help you,” Beltran said to each of his teammates after joining the team in early 2017. “Even if it looks like I’m busy, you won’t bother me. If you sit down next to me and ask me a question, I would be more than happy to give you the time that you need.”

Justin Verlander was the splashy trade deadline acquisition that anchored the Astros championship rotation. George Springer swung the big bat that hit five home runs in the World Series on his way to MVP honors.

But like so many successful teams, the most critical players often aren’t the most talented. They’re the Carlos Beltran’s that can bring teammates with different backgrounds together, enforce a high-performance culture and drive a team to an outcome that’s greater than the sum of the parts.

How does a baseball team, a hockey team, or any organization go about finding their Carlos Beltran?

That’s the subject of our next book, The Captain Class, by Sam Walker.